The American South was originally inhabited by Native American tribes that were here long before the arrival of Europeans and the establishment of colonies in places like Jamestown and Charleston.

In the Carolinas, it was mostly Cherokees, while the Creek tribes inhabited Georgia and Alabama. They had their own government and language and mostly existed peacefully without outside interference as autonomous nations.

What Was the “Trail of Tears?”

But the discovery of gold in the region in the early 1800s led to a movement of taking ancestral lands for monetary gain. In 1830, President Andrew Jackson passed the Indian Removal Act, allowing the ceding of these lands for the government.

After being removed from their homes in North Carolina, Georgia, Tennessee, and Alabama, the Native American tribes, made up of over 16,000 people, were placed in eleven internment camps, mostly in Tennessee.

Here they waited to be sent on the 800-mile journey west, which would become known as the “Trail of Tears.” Between 1838 and 1839, thousands died of disease and dehydration. This tragedy disproportionately affected the tribes in the modern-day South, including Alabama, Arkansas, Georgia, North Carolina, Kentucky, and Tennessee.

The Trail of Tears National Historic Trail was established, stretching over 5,000 miles and nine states. Along the way are historic landmarks and informational markers commemorating this forced removal through 17 detachments.

It can be traveled many different ways in one trip or in many smaller trips. This particular post is important to me because my family background includes both Native Americans and the people that removed them.

Trail of Tears Sites in the South

Georgia

North Georgia has a long legacy of Native American history, specifically Creeks and Cherokees, as well as Mississippian burial mounds. But it quickly became the setting for many roundup sites, where tribes were forced into camps for further relocation. They were separated into multiple routes west.

New Echota State Historic Site near Calhoun was home to the capital of the Cherokee Nation starting in 1825 until the tribe’s removal in the 1830s. Here, the tribal council constructed a council house, supreme court, and the offices of the first Indian language and Cherokee newspaper.

After removal, the area became a ghost town for more than 100 years. In 1954, the Georgia Historical Commission began its first excavation of the site. Many of the buildings were later restored or reconstructed.

Near Rome is the Chieftains Museum/Major Ridge Home, where Major Ridge lived in 1800 with his Cherokee wife. He sided with Cherokee forces in the War of 1812 and was given his title by Andrew Jackson.

But through Jackson’s Indian Removal Act, Ridge’s land was given to another person. Ridge and other Cherokees signed the Treaty of New Echota, ceding territory to the United States and agreeing to move west, a controversial decision that led to his demise. The home is open as a museum and was the first private site added to the Trail of Tears National Historic Trail.

The Cedartown Cherokee Removal Camp was where the local Cherokee were brought in 1838 before they were taken to larger camps in Tennessee. It was the southernmost military post during this process.

Today, it has two outdoor exhibits that tell about the history from this period. The Fort Wool site is on private property, but a marker at Fort Cumming in Lafayette describes the stockade here that housed Cherokee prisoners. The site of Fort Newnan, another camp, has been lost to time.

North Carolina

Another site of roundups was Western North Carolina, the ancestral lands of the Cherokee. Fort Lindsay, Fort Butler, and Fort Delaney were the main sites of internment for these tribes. Fort Lindsay was the northernmost camp and, due to the uneven terrain, some people in Nantahala were able to avoid capture by hiding out.

A marker near the Almond boat ramp tells about this history and another marker describes Fort Butler. At Fort Delaney, a small hospital and blacksmith shop were located along with the housing for the detainees, but all that remains now is markers.

The Cherokee County Historical Museum in Murphy is a good place to start learning about the Cherokee culture, including over 2,000 artifacts from the tribe and panels interpreting the history. The town of Cherokee is the modern home of the Eastern Band, on what is known as the Qualla Boundary.

The people that live here today are the descendants of people who made their way back from the reservations in Oklahoma or evaded capture. It’s now a sovereign nation with over 14,000 members. Learn about these people at the Museum of the Cherokee Indian, the Oconaluftee Indian Village, and the seasonal outdoor drama “Unto These Hills.”

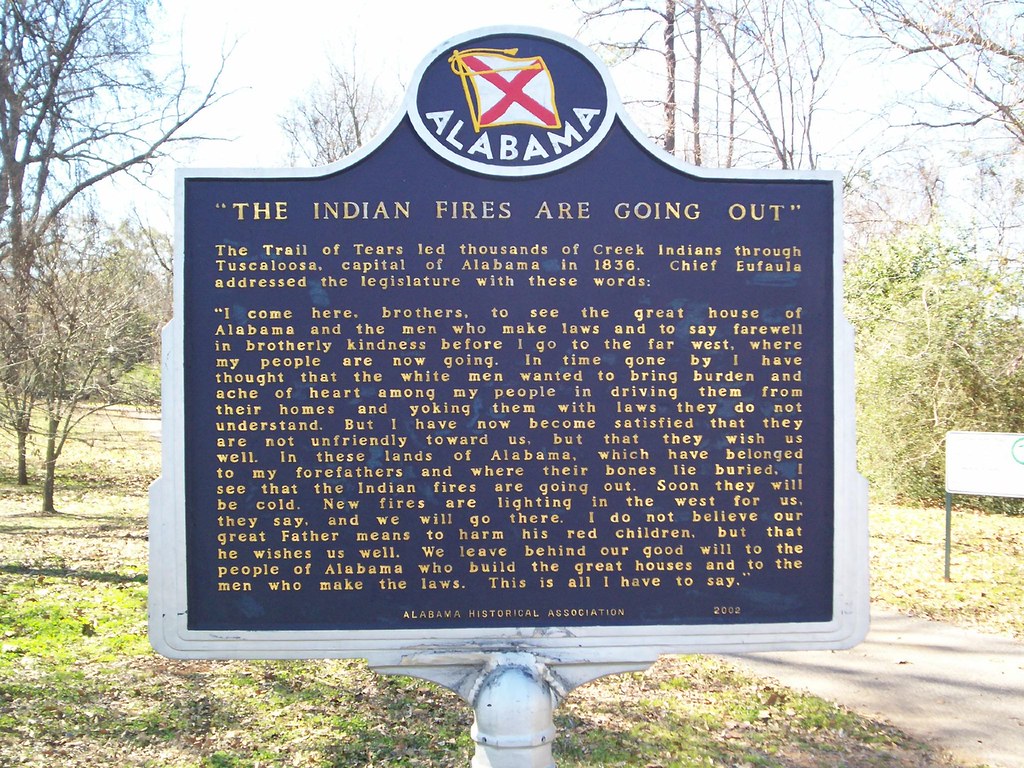

Alabama

After being held mostly in Tennessee, some Native Americans were taken mostly via two Southern routes through Alabama, the Drane and Deas-Whiteley routes. Others took the Benge Route, which started in Fort Payne, stopped in Guntersville and Huntsville, went north to Tennessee and then onward to Missouri, near the modern Trail of Tears State Park. It doubled back south to Arkansas, where the journey ended.

Sequoyah lived near Fort Payne, then known as Will’s Town, for a time, where he developed the written Cherokee language. This area was also where one of the stockades was located. An old chimney and historic markers are all that remain today.

The three main sites on the historic trail are the Andrew Ross Home, Fort Payne Cabin Site, and the Willstown Mission Cemetery. The Andrew Ross Home was owned by a Cherokee judge and is privately owned.

The Fort Payne Cabin site is under construction, but the Willstown cemetery is open to the public, where there was once a Cherokee council ground with a school, log cabin, and the burial sites of at least 40 Cherokee.

The overland water route, which traced the Tennessee River north, passed through modern-day Sheffield, one of the towns that make up Muscle Shoals, at Tuscumbia Landing. Low water levels forced them to take trains part of the way.

To the north at Waterloo Landing, the detachments boarded a steamboat bound for “Indian Territory.” Pay your respects at Tom’s Wall, a memorial to a Yuchi woman who followed the sound of the “singing river” back to her homeland.

Tennessee

Tennessee was the site of the majority of these internment camps, especially in the eastern part of the state around Chattanooga. It was here that four of these water detachments took 3,000 Cherokee, many of which didn’t make it, up the Tennessee River, then transferring to the Ohio to the Mississippi to the Arkansas rivers.

Charleston, Tennessee was the site of Fort Cass, where over 9,000 Cherokee were held, the largest of all the camps. Before the removal act, it was the site of a “Cherokee agency.” But even before the forced removal, diseases like whooping cough and dysentery were rampant, killing people every day.

Over 600 Cherokee left via the Bell Route, led by John Bell of the Treaty Party, ending in Evansville, Arkansas. No reminder exists of this site. The Hiwassee River Heritage Center is the only place with exhibits focusing on this particular camp.

Red Clay State Park near modern-day Cleveland features a natural spring that was used by Cherokee during council meetings. Today, it features over 200 acres, including replicas of 19th-century Cherokee buildings. The visitor’s center has exhibits on the Native people and their removal.

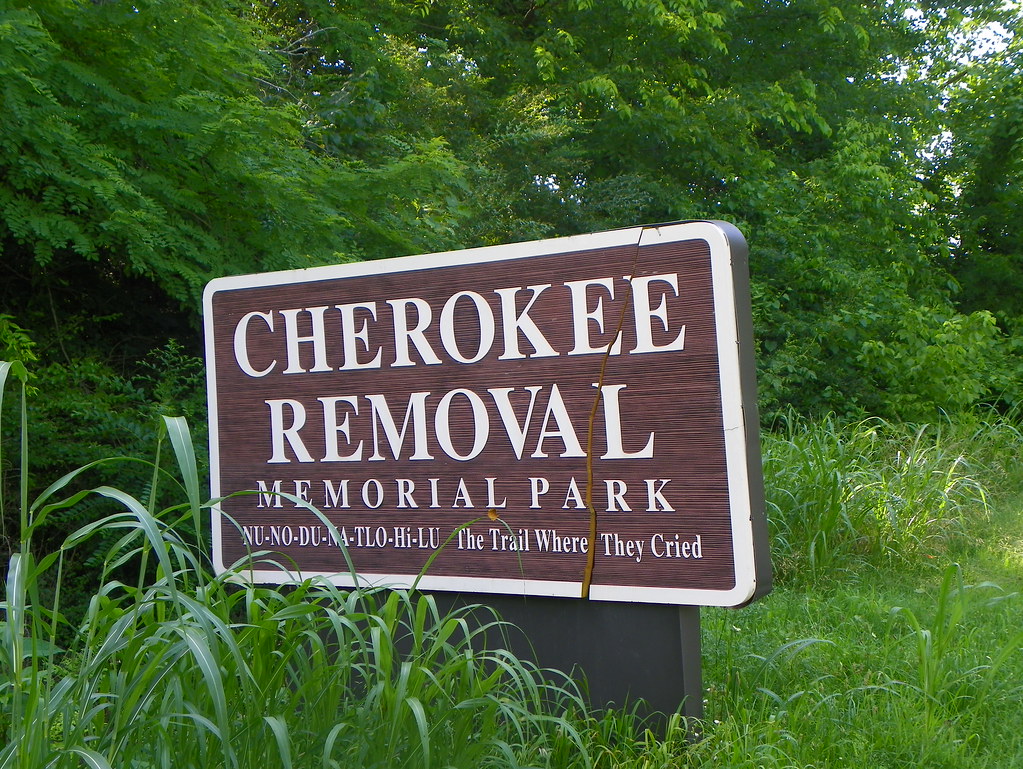

Nearby Blythe Ferry was the site of where 10,000 Indians had to cross Tennessee River. The Cherokee Removal Memorial Park has a visitor’s center and memorial to the lives lost. The Sequoyah Birthplace and Museum in Vonore, not far from the Smokies, memorializes the Cherokee leader that created the written language and continued with his people on the Trail of Tears.

Ross’s Landing, which is present-day Chattanooga, was a major embarkation point for the Trail of Tears. The location is along the river in front of the Tennessee Aquarium. Named for John Ross, a Cherokee chief, there is an art installation to memorialize the Cherokee, made by members of the tribe from Oklahoma.

Little remains from the Cherokee time in this part of Tennessee, but Moccasin Bend National Archeological District, part of Chickamauga and Chattanooga National Military Park, is part of the Cherokee route west.

A small memorial at Pulaski’s Pleasant Run Park is the only reminder of the Cherokee that passed through town on the Bell and Benge routes. They also have an interpretive center and a statue devoted to the Cherokee people. The Bell Route also bisected the state, passing through Savannah and Memphis, Tennessee. In Savannah, the Tennessee River Museum has exhibits on the Trail of Tears.

The Northern Route left from Charleston, cutting north. At the Stones River Battlefield, which is known primarily as a Civil War battlefield, are two exhibits that cover the two Northern routes that passed through here. The Hermitage, outside of Nashville, was the home of Andrew Jackson, the man behind the Trail of Tears.

In fact, the Northern Route passed near his home. Near the Victory Memorial Bridge is where thousands of Cherokees crossed the river. All that you can see is the abutments. Near Port Royal State Park is the site of a stagecoach stop and later the last encampment in Tennessee before continuing north.

Arkansas

This state is where most of the routes came together before crossing the border into Oklahoma. At the end of the trail’s Bell Route is Village Creek State Park, the site of a road that connected Memphis to Little Rock.

It was here that Creek and Chickasaw peoples were removed. The Cherokee later passed through here. A small museum interprets the history. In Helena, the Delta Cultural Center has exhibits on Quapaw tribes that were removed.

The North Little Rock Riverfront Park was where a number of these routes converged. Seven interpretive panels discuss the Four Civilized Tribes and the Cherokee Removal. The Cadron Settlement Park, north of Little Rock, was originally a French trading post and later had four Cherokee detachments.

Interpretive signs describe the Trail of Tears to visitors. The Bell Route joined Drane route and continued to Russellville, Van Buren, and Evansville. The area around Lake Dardanelle State Park in Russellville is where the Western Cherokees had set up their society, but also where the five tribes were brought during removal. A visitors center interprets the significance of the area.

The overland water route, which followed a similar path as the Bell-Drane routes, continued to Fort Smith National Historic Site near Van Buren. The army fort was the site of Cherokee water detachments and later internment of Creeks, Chickasaws, Choctaws, and Seminoles. The visitor’s center at this site has exhibits on the removals. This route continued onward into Oklahoma and established a Cherokee capital in Tahlequah.

On the Benge Route, which started in Alabama before passing through Missouri, the groups doubled back south to Arkansas, including in Batesville and Fayetteville, where a memorial park has been established.

Kentucky

The Trail of Tears passed through only a small portion of Kentucky, mainly the southwesternmost corner north of Nashville. The Cherokees on the Northern Route started in Charleston, Tennessee and continued to a few stagecoach stops, now mostly private property.

The area in Hopkinsville now known as Trail of Tears Commemorative Park was used as an encampment and is where two Cherokee chiefs, Fly Smith and Whitepath, were buried after dying during removal. It now contains a memorial and interpretive center covering the history of the Cherokee Nation.

At Big Spring in Princeton, most of the Cherokee detachments stopped here on their journey. Historical markers now educate visitors on the spring, the early roads, and the Trail of Tears. At Mantle Rock Preserve near the town of Joy, is where over 1,700 Cherokee were forced to camp until the Ohio River melted enough to cross.

It’s now a protected park but is open to the public for its hiking trails. Thousands of Cherokee boarded flatboats to finally cross at Berry’s Ferry. No remnants exist from the ferry site, but there are some pieces remaining from the homesite of John Berry, who operated the ferry. Other detachments stopped along the river in Paducah and Columbus. From here, they crossed into Illinois, Missouri, Arkansas, and then Oklahoma.

PIN IT

This is a well written and expertly researched article regarding the Trail of Tears. I am also a descendent from “both” sides. Most people don’t realize the complexity behind the issues of that time period. Some fault the Treaty Party but they saw the intent of the Georgians and did everything possible to to ensure new land and compensation. Unfortunately there were leaders who gave false hope which delayed the migration into the winter with tragic results. Many including my family lost land and loved ones in this tragic event. Thank you for sharing your knowledge of the specific pathways and historical markers.

Thanks for great article…one of the trails comes down my driveway on Walden Ridge, northeast of Chattanooga. Dr. Don Nichols, Pikeville, TN